Facade

Solo exhibition

Galeria Silvia Cintra + Box 4, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014

Façade, video projected on plexiglass screen, 3min, loop, 2014

The exhibition Facade takes as his point of departure a milestone in Brazilian modern architecture: the Gustavo Capanema building, the former Ministry of Education and Culture in Rio de Janeiro. Constructed between 1936-1945, it was designed by a team of architects, including Lucio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer, Eduardo Reidy, Carlos Leão, Ernani Vasconcellos and Jorge Machado Moreira with the assistance of the French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier. The building also features collaborations with artists, who each created work for the interior and exterior areas. Paradoxically, however, these left-leaning architects and artists conceived the building in the midst of Getúlio Vargas’s regime (1930-1945), which established the Estado Novo in 1937, initially of fascist inclination. Thus the building embodies a contradiction: the architecture represented a system based on democratic values and at once responded to the regime’s vision of a modern nation.

As an exhibition, Facade includes four main elements: a phrase cast in bronze, a film, a wall-mounted framing system, and an enlarged postcard image from the 1950s. Key to the installation is the film of the building’s facade. In a single take, the camera travels in a vertical line from the ground floor to the building’s roof terrace and beyond, revealing the city, the sea, and the horizon. In this shot one sees how Corbusean functionalism meets local elements, from finishing materials to a landscape design with tropical plants. The transparent windows provide visual access to the interior spaces, while the sudden appearance of a blue protective cover on the facade signifies its current renovation.

In collaboration with exhibition designer Birger Lipinski, Redondo designed a wall-mounted framing system that mirrors the window grid of the building’s facade. In this way, the structural qualities of the Capanema building’s architecture also inform his work’s formal articulation. This wooden framework displays screen prints on wooden panels, which picture a selection of the artist’s contemporary photographs of the building. Redondo juxtaposes various visual details from the site, including Vargas and Capanema portrait busts, wall paintings by Cândido Portinari, the Brazilian flag, among other images and spaces that speak to the building’s complex history and iconography. These fragments, as well as their collage-like effect on account of their placement and display, evoke the contradictory legacy of how distinct ideologies came to be performed in this same physical space. By revisiting the building’s history (which includes the Good Neighbour Policy between the U.S. and Brazil in the 1940s), Redondo also prompts us to think about Brazil’s current economic expansion and increased global visibility.

The exhibition also addresses how the Capanema building was originally the Ministry of Education and Health, whose political program was premised on the development of a modern and “healthy” nation. In response to this history, Redondo printed and enlarged an emblematic postcard image from the time, which shows an athlete posing in front of the building. Rather than a seamless reproduction, the artist distributed the image across various pieces of plywood, which at times recall the shapes and sizes of protest posters. The original drawing’s parading of heroic strength conjures the importance that sports were given during the creation of a modern Brazil. But such symbolism and forms also have purchase on the present: sporting events such as the World Cup and Olympic Games are having great impact on the socio-economic development of the city today, also provoking civil unrest.

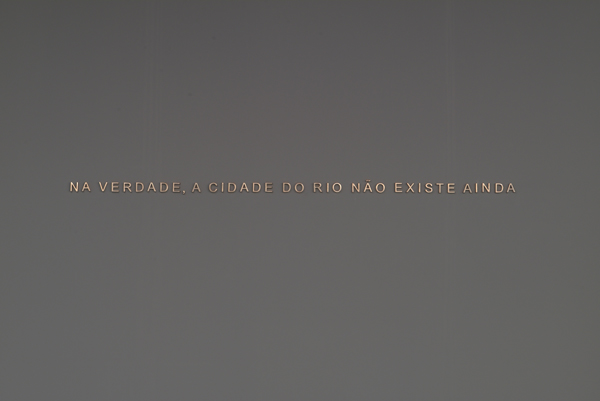

Finally, located on the gallery’s far wall is the cast phrase Na verdade, a cidade do Rio não existe ainda (In reality, the city of Rio does not exist yet), which was lifted from a sketch made by Le Corbusier during his trip to Rio in 1936. The phrase speaks to the way Modernism was perceived as an ultimate solution for development without, however, taking into consideration local realities. Yet as with the image of the heroic athlete sited across from it, one can also read Le Corbusier’s words in relation to the contemporary moment and the city’s drive for the future. By overlapping different temporalities and various elements that all come together in this signature landmark building, Redondo’s work reactivates a vision on the history of politics. In so doing, he creates a space for the viewer to assess the complexity of historical memory and its ambiguities from different perspectives. Facade suggests the variegated historical context of the Capanema building’s construction and the possible meanings of the facade’s afterlife today.

Video:

Camera: Gabriel Klabin / Editing: Daniel Frony

Photos:

Mario Grisolli